Thursday, October 27, 2005

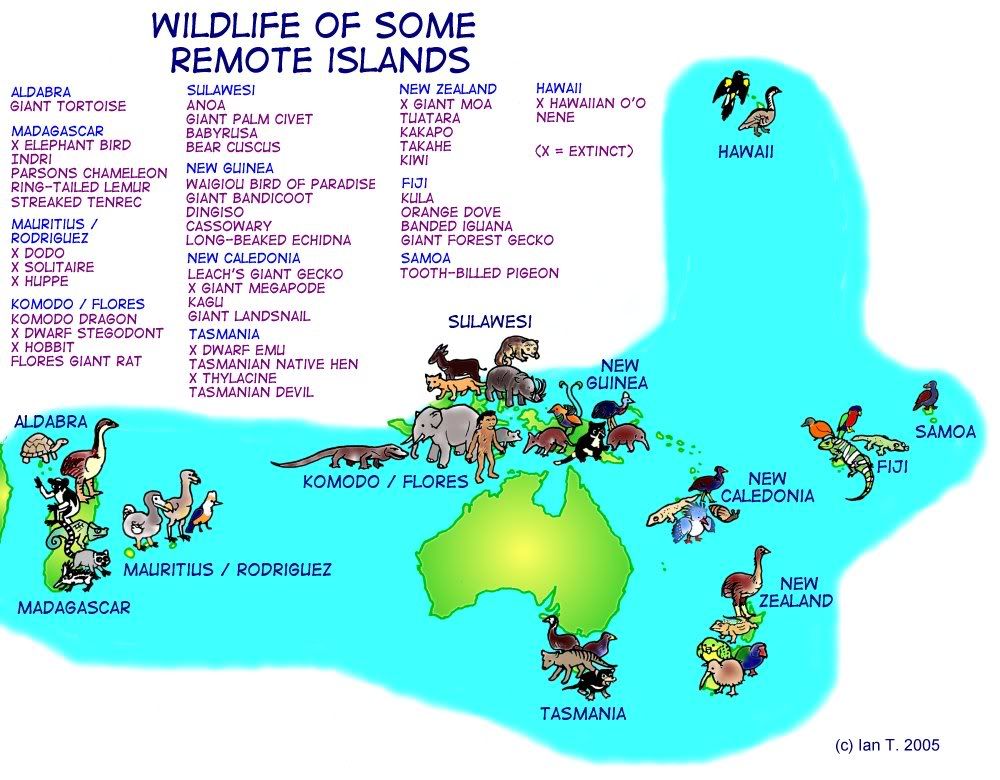

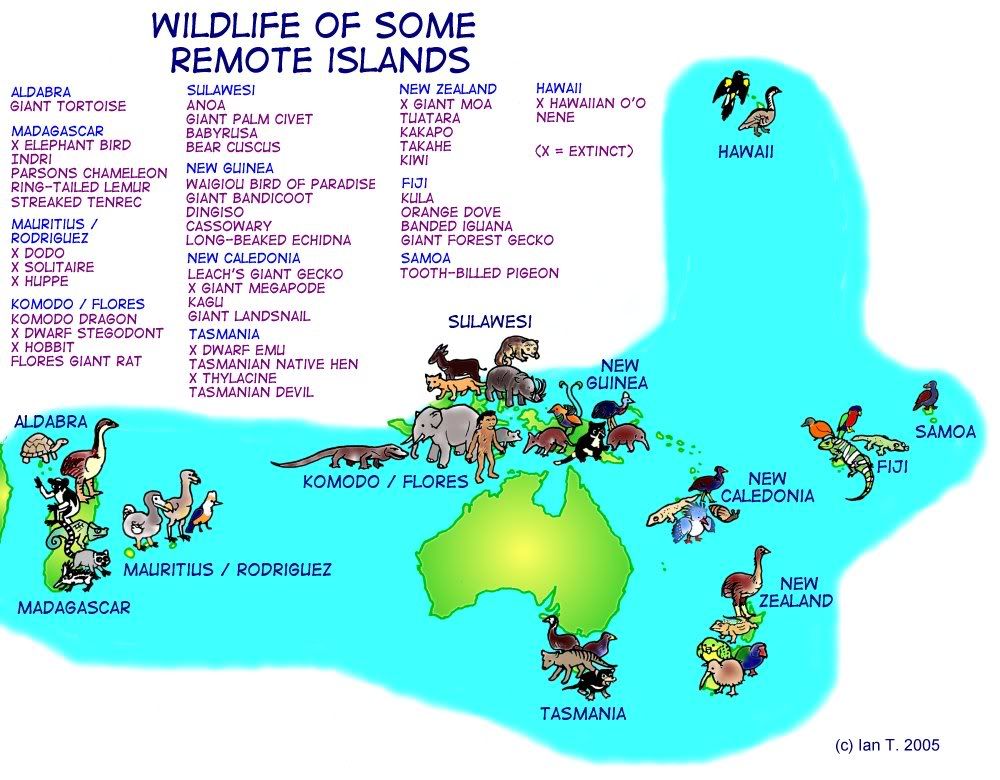

Remote for Illustration Friday

Please click on picture and resize for larger version:

For me, "Remote" really brought up the concept of geographical isolation. Two excellent books have gotten me thinking about island zoology and biodiversity again: David Quammen's The Song of the Dodo and the beautiful photographic book South Sea Islands: a Natural History by Rod Morris and Alison Ballance. I also had a number of Tim Flannery's books in mind while composing this.

This is very much an Illustration (complete with explanatory text) rather than a work of art :). I've wanted to do maps along these lines for a while. This is actually pared down a lot - I took out quite a few, such as the Galapagos Islands, French Polynesia and even The Falkland Islands - just to make it smaller. In a sense it covers a lot of the ground followed by great naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, the other, somewhat forgotten evolutionist whose observations in these regions brought him to the same conclusions (at the same time) as Darwin. The Southeast Asian cutoff is along the Wallace Line.

I remember a long time ago looking at pictures of eastern and western spinebills and noticing how clearly their diversification - different realizations of the same pattern - showed evolution in action. Nowhere is speciation made more clear than on remote, isolated islands. These places have to "make do" with the species that get there, either by being cut off from main landmasses at some point (allowing for the survival of primitive, relict families), or by being reachable only by swimming, flight or floating on vegetation. Following this haphazard species arrival fauna evolves into the available niches, though usually following a pattern of dwarfing of large species and enlarging small ones.

Of course, this all changes when modern people arrive, leading invariably to the high extinction rate among island species. For that reason, quite a few of the creatures shown here are extinct in comparatively recent times. However, many of them do still survive - at least until the Greenhouse Effect gets worse - and these include some of the most bizarre birds and beasties.

There is also inter-relationship between many of these species, such as the dodo and solitaire (and those mourning the dodo might like to look closely at the tooth-billed pigeon of Samoa). These three are clearly pigeon family descendants - other "arrival" species evolved from mainland species include the Fijian banded iguana and the Nene (Hawaiian goose), evidently evolved from the green iguana and Canada goose respectively.

And then there's Australian mainland - which is a study of geographical isolation all on its own - but outside the parameters I set myself here :).

For me, "Remote" really brought up the concept of geographical isolation. Two excellent books have gotten me thinking about island zoology and biodiversity again: David Quammen's The Song of the Dodo and the beautiful photographic book South Sea Islands: a Natural History by Rod Morris and Alison Ballance. I also had a number of Tim Flannery's books in mind while composing this.

This is very much an Illustration (complete with explanatory text) rather than a work of art :). I've wanted to do maps along these lines for a while. This is actually pared down a lot - I took out quite a few, such as the Galapagos Islands, French Polynesia and even The Falkland Islands - just to make it smaller. In a sense it covers a lot of the ground followed by great naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, the other, somewhat forgotten evolutionist whose observations in these regions brought him to the same conclusions (at the same time) as Darwin. The Southeast Asian cutoff is along the Wallace Line.

I remember a long time ago looking at pictures of eastern and western spinebills and noticing how clearly their diversification - different realizations of the same pattern - showed evolution in action. Nowhere is speciation made more clear than on remote, isolated islands. These places have to "make do" with the species that get there, either by being cut off from main landmasses at some point (allowing for the survival of primitive, relict families), or by being reachable only by swimming, flight or floating on vegetation. Following this haphazard species arrival fauna evolves into the available niches, though usually following a pattern of dwarfing of large species and enlarging small ones.

Of course, this all changes when modern people arrive, leading invariably to the high extinction rate among island species. For that reason, quite a few of the creatures shown here are extinct in comparatively recent times. However, many of them do still survive - at least until the Greenhouse Effect gets worse - and these include some of the most bizarre birds and beasties.

There is also inter-relationship between many of these species, such as the dodo and solitaire (and those mourning the dodo might like to look closely at the tooth-billed pigeon of Samoa). These three are clearly pigeon family descendants - other "arrival" species evolved from mainland species include the Fijian banded iguana and the Nene (Hawaiian goose), evidently evolved from the green iguana and Canada goose respectively.

And then there's Australian mainland - which is a study of geographical isolation all on its own - but outside the parameters I set myself here :).

Labels: Australian wildlife, cryptozoology, David Quammen, Illustration Friday, island wildlife, new animals, Tim Flannery